The Jazz Singer (1930)

by Giancarlo Gonizzi

It was raining. I still remember it, after so many years, it rained like a deluge.I had taken a train in Parma and was going to Genoa. It was November and it was cold. The countryside, half-flooded for the abundant rain, was something that made you melancholic.

After almost three hours of travel, I arrived in Liguria. I was hoping that, beyond the Apennines, the weather would be better. But nothing. I found a wall of water. A taxicab brought me to my destination: an antique dealer I had met a few weeks earlier at the Parma fairs, who had bought a sampler of the Zafferri Graphic Shops of Parma. At the fair, he had a large number of pencil sketches of posters from the 1920s and 30s: I looked at them with attention, but saw nothing that could be connected to Barilla.

I asked where they came from: it was not a company archive, but that of a drawing artist from Parma, Raoul Allegri (1905-1069). After graduating brilliantly from the “Paolo Toschi” Lyceum of Arts, in 1928 he opened the “Allegri Advertising” Studio on Vittorio Emanuele Street 133 where he worked for a decade, before devoting himself to teaching. He made advertising announcements for Borsari, labels for OPSO, posters for VOV by Pezziol and the Zanlari shoes, press releases for several conserve industries of Parma, which were prevalently printed by the Zafferri Brothers Shops, with whom he had a collaboration.

Ferdinando Zafferri had introduced the technique of lithographic printing in Parma, between 1899 and 1900. His grandchildren Gaetano and Alberto developed the activity enormously and strategically moved to Palazzo Mantovani near the railroad station plaza, where they gave work to about one hundred employees. The Zafferri Graphic Industries became successful at national level in the sector of commercial printing (having the railroad at a few yards distance helped), by producing labels and packaging for a number of Italian pasta factories: in addition to Barilla, also Amato, Braibanti, De Cecco and Voiello.

In those times “Réclame” – so was advertisement called – worked in a very different way than it does today: illustrators invented striking images, prepared them without logos and then offered them to potential clients. These were personalized only after they were purchased.

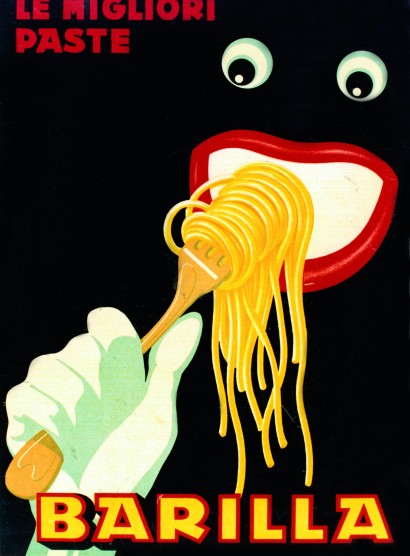

Allegri, who had been working for some time with Zafferri and knew the clientele of pasta industries of the graphic studios, set up a truly unusual promotional poster. The antique dealer, who at the fair remembered only that he had something from Barilla at home, had later described this on the phone, leaving me baffled: a black man eating spaghetti, with the writing Barilla in red and yellow letters.

And this was not a sketch, like those I had seen at the fairgrounds, but a shop poster printed as a lithograph. Therefore, a poster that had actually been produced. There was no trace of it in photographs nor in the surviving documentation of the Historical Archives. What was it about? It is true that Barilla exported to the Italian colonies in Eastern Africa, but this was a peculiar subject. With these thoughts in my head, I reached my destination.

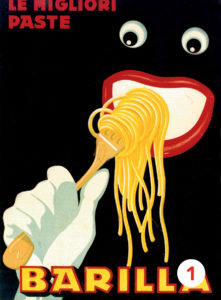

In spite of my umbrella, the few meters between the taxi and the main entrance granted me a cold shower. The antique dealer kindly helped me to dry out. Then, he showed me the poster: étonnante – amazing, as the French say – in its simplicity. From the black background, two eyes, red lips and a hand in a white glove holding a fork with golden spaghetti emerged (photo 1).

My journey was worthwhile. The good-hearted antique dealer – I probably had the aspect of a wet chick – insisted to bring me to the train with his car to save me from another stronger shower. Water was my travel companion during my entire return journey to Parma, deep at night, while my mind was lulled by a jazzy sounding theme…

What I discovered later, studying that image, was truly astounding. On October 6, 1927, the American cinema industry launched sound in movies, which up to that point were silent and accompanied live by pianists. These underlined the most dramatic passages live while signs with short phrases followed the lines of the actors. Now, technology made it possible to listen directly to the voices of the protagonists.

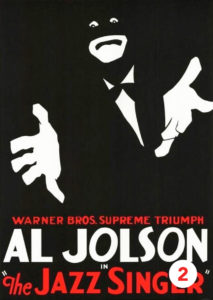

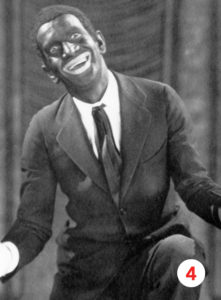

The Jazz Singer (photo 2) by Alan Crosland was the first “talkie” of the history of cinema: it was interpreted by Jewish actor and composer Al Jolson (1886-1950), (photo 3) wearing make-up to look like a black singer (photo 4). A few spoken lines and nine songs were able to save Warner Bros, the production studio, from the economic difficulties of the times. History was turning a page. Thus, that figure would remain like an icon in the collective imaginary and decade after decade was repeatedly proposed by cinema, showbusiness and advertising and from time to time would be associated with different situations and products, transmitting it to our days.

Thanks to the help of Peppino Calzolari (1924- 2017), a cinema historian, I discovered that the film was shown in Parma on March 9, 1930 at Supercinema Orfeo with an unprecedented success, given the novelty of sound. Likely, on the wave of that happening, the painter, with a few well placed blotches of color, declared his enthusiasm for the fashion of the Roaring Yeas: in the association with Barilla pasta, besides the echo of the American myth, an homage to the modernity and the international character of the industry from Parma can be guessed.

It is a piece of history that meets the century old history of Barilla in an extraordinary way, and, in spite of the insistent rain, we were able to bring it back home.