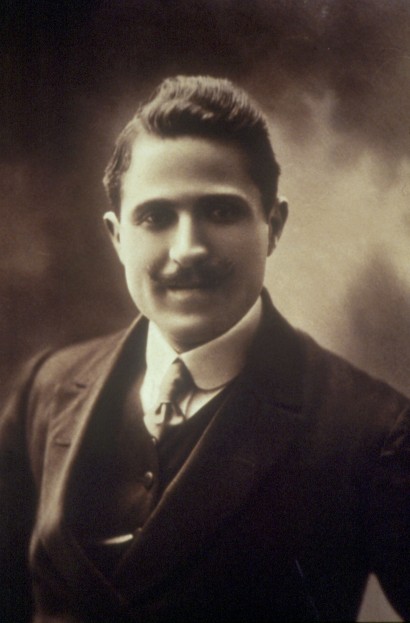

Pietro Barilla senior

Parma, 3 May 1845 – 17 August 1912

Pietro Barilla Senior (to distinguish him from his grandson, also named Pietro) was born in Parma on 3 May 1845, the sixth of the ten children of Ferdinando, known as Luigi, and Angela Julia Lanati. Alongside his elder brothers Ferdinando and Giuseppe, Pietro soon went to do his apprenticeship in the workshop belonging to his maternal grandfather Vincenzo Lanati, a baker who had a shop and bake-house in Strada Santa Croce 183-185.

Having finished their period of apprenticeship, all three brothers remained in the sector: Ferdinando continued working in the Lanati bakery; Giuseppe married Emilia Sivori, daughter of the baker Giovanni, and set up a pasta workshop in 1873. Lastly, Pietro, in 1877 opened the bread and pasta shop in Strada Vittorio Emanuele 252 that was at the origin of the future G. & R. Barilla Company that his sons Gualtiero and Riccardo would run as of the first decade of the new century. In the Chamber of Commerce’s registration book for the year 1877, Pietro Barilla is indeed enrolled as a ‘manufacturer of bread and pasta’. In the workshop in Via Vittorio Emanuele (now Via della Repubblica 88), near the church of San Sepolcro, production was still carried out using artisan methods. The equipment used, perhaps only a kneading machine and a press, were made of wood and produced locally. The business was barely sufficient to maintain the family.

The work, which was carried out during the night so that customers could be offered fresh bread from the first light of dawn, was laborious and moreover was regulated by a fairly binding legislation both as far as the quality of the flour used was concerned and with regard to the type of baking. The pasta, naturally, could be processed and produced by day, but for it too, there were fairly stringent regulations in force. Given the social importance that the production of bread and pasta assumed, then as now the fundamental foodstuffs of the Italian population, the bread and pasta-making business was subject to rigorous controls by the authorities, as well as to conflicts and pressures in the particular case, which was extremely frequent in the last decades of the 19th century, of bitter trade-union disputes that were not of short duration. In these emergencies, Pietro sat alongside the other major bread and pasta manufacturers in the city to discuss trade-union problems that impacted on night work, to negotiate price controls and measures suited to protecting, with the support of the Chamber of Commerce, an activity that in those years had become of great importance for the economy of the province, bearing in mind that a certain quota of the pasta production was already being marketed outside Parma at that time.

The economic situation of the Barilla family in that period was certainly not prosperous and can be inferred from the tax rolls, which – given the statistical limitations of the findings – do, however, give a proportional idea of the importance of the various taxpayers. The three brothers Ferdinando, Giuseppe and Pietro reported an income which, compared to that of other tradesmen at that time, is about average, perhaps a little more in the case of Giuseppe, who declared 2,200 liras, whilst the other two only declared 1,800 liras. This was nothing like the 20,000 liras declared by the miller, baker and pasta maker Fiorenzo Bassano Gnecchi. Almost all the other bakers and pasta manufacturers, on the other hand, were below 2,000 liras.

This category, therefore, was not a particularly profitable one: the profession of baker, carried out using artisan methods with the sole help of family members was one of pure subsistence.

The year before enrolling with the Chamber of Commerce – a formality which in those days was usually carried out belatedly in relation to the actual opening of the financial year – on 27 July 1876 he had married Giovanna Adorni, who was to give him six children: Aldina (1877), Ines (1879), Riccardo (1880), Gualtiero (1881), Socrate (1885) and Gemma (1888). They all survived apart from Socrate, who died when he was still a newborn baby.

Pietro Barilla senior is remembered as a man who, albeit of a modest nature, possessed organizational skills and was tenacious in pursuing the goals he had set himself, gifted with a spirit of sacrifice, enormous intuition and remarkable social open-mindedness.

There is no doubt that in him it is possible to detect that epic sense of enterprise that fascinates today’s historians, who look not only at the purely economic aspect in entrepreneurial activity (the search for profits), but also at the realization of a vision, of a dream, the way in which an entrepreneur embodies his idea, winning faith in it and infecting others with his actions even before they have been carried out. It is this enthusiasm for enterprise, for risk-taking, for the ceaseless quest of innovation that places the entrepreneur above and beyond the economics of the figures on a balance sheet alone, and it is this characteristic that can be perceived in Pietro Barilla Senior and in his children and grand-children who would continue with his original idea in the same spirit.

In 1892, Pietro wanted to expand his turnover: he put the shop in Strada Vittorio Emanuele 252 in his wife’s name and bought a second shop in his own name in Borgo Onorato, where the products from the main bake-house were sold. As a result he subjected himself to an exhausting pace of work, but profits did not prove to be sufficient to cover the investment. On 26 June 1894, to save what could be saved from the onslaught of his creditors, he arranged for his wife to wind up the business in her name and opened up another one in the same street, Strada Vittorio Emanuele, at number 262, and on 3 July 1894 Pietro Barilla was forced to declare bankruptcy and give up his second shop. However, he was still not 50 years old and his time to retire had not yet arrived.

He continued to work in his wife’s shop, to seek out new initiatives, to plan innovations and modifications in order to adapt the production to the ever changing tastes of the public.

In 1898, after several years of hard, tenacious work, his finances improved to the point of allowing him to expand the warehouse for the raw material, flour. With the use of a small wooden press he superseded the manual production phase and made it at least partly mechanical; then, at the turn of the new century, he replaced this rudimentary piece of equipment with a cast iron press and a kneading machine with a revolving plate. As a result he increased the production of bread as well as that of pasta, which immediately went up to two quintals a day and already by 1903 had doubled. In 1905, with the engagement of five workers, the business reached a production of twenty-five quintals of pasta and saw a proportional increase in that of bread. Meanwhile, on 27 May 1904, his wife Giovanna died and it was therefore necessary to hand over the reins of the business to his sons Gualtiero and Riccardo. Before the moment of his death arrived, on 17 August 1912, Pietro senior had the satisfaction of being able to see the birth of his first grand-daughter, Riccardo’s daughter, baptized with the same name as her grandmother, to witness the opening of the new factory outside Barriera Vittorio Emanuele and thus to leave both his family and his Company, to which he had dedicated years of commitment, of dreams and hopes, and also seen – and why not – some failures and disappointments, in excellent hands.

Ubaldo Delsante

Sources and Bibliography

CCIAA, Matricola degli esercenti commercio arti e industrie nel Comune di Parma (from 1877 onwards).

Ministero dell’Agricoltura, Industria e Commercio, Le condizioni industriali di Parma (1890), ried. CCIAA, Parma-Bologna, Analisi, 1991, pp. 39-43.

BARILLA Riccardo, La storia della mia vita dal giorno che sono nato, mss. n.d. and Alla mia cara consorte ed ai miei cari figli, mss. of 14 Dec 1942, in ASB.

CASTELLI ZANZUCCHI Marisa, Piccola storia di un grande forno, in Barilla: cento anni di pubblicità e comunicazione. Milan, Pizzi, 1994, pp. 60-62.