Diffusion and variety of an architectural typology

Even though the construction of the Pavesi Autogrill chain represented an economic and social phenomenon of noteworthy relevance in Italy, it should not go unnoticed that the history of contemporary architecture treated in a very marginal way the description of these works, in some instances, maybe in the post-modern revaluation of a generic Italian highway “landscape” observed at the most for its phenomenological implications rather than for the fact it belonged to the typology of city building through architecture.

It is a fact that these buildings were left out of the most authoritative research of the years of economic reprise after World War II. Immediately before, in the years of Reconstruction, the traditional masonry technique was progressively converted into a modern“Neo-Realistic” language for some aspects, especially evident in the first residential INA-Casa neighborhoods, according to specific Italian characteristics of interpretation of the Modernist Movements that became famous worldwide through the works of architects that had already been very unconventional experimenters in the cultural landscape of the years preceding the war: Albini, the BBPR ( and the writings of Ernesto Nathan Rogers), Quaroni, Samonà, Gardella, Ridolfi, that can be contextualized also in the works of a culturally engaged entrepreneur like Adriano Olivetti.

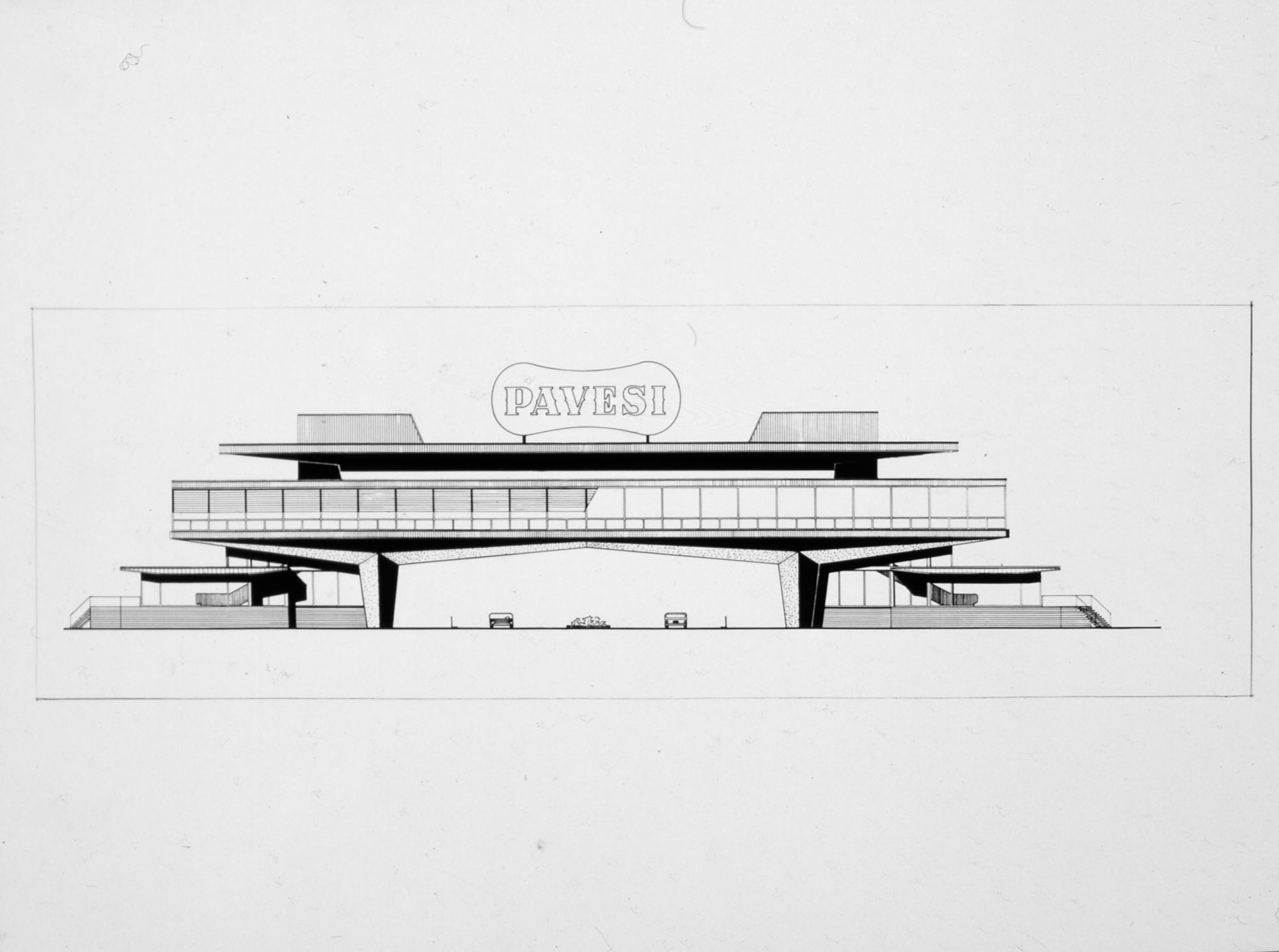

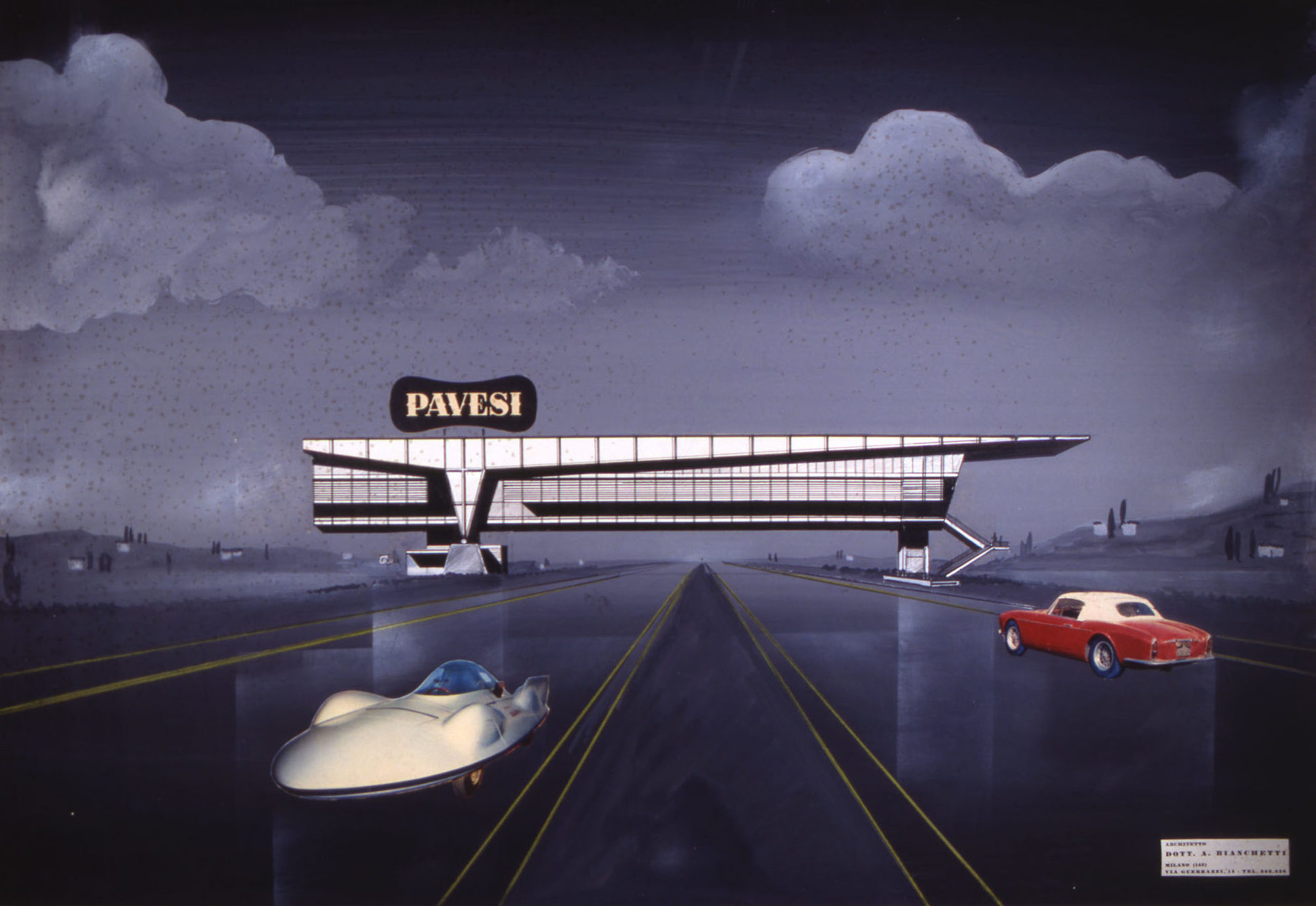

The buildings by Angelo Bianchetti for the Pavesi Autogrills designed like bridges crossing the highway are far from this cultural landscape, and were born in the context of those forms of entertainment and leisure time activities brought on by the economic prosperity and by the idea of progress linked to the euphoria of speed and of car travel.

Nonetheless these buildings deserve to be considered as works of art at least for two reasons. First of all, because the technological gradient follows the criteria of experimentation of shapes and structural frames in the exposure of beaming, in the projections of the shelves, in the wide, light, and transparent continuous windows, in the slim metal frames well designed to support the advertising billboards: a criteria embedded in the history of architecture whose roots are founded on a continuity of thought and on a modern “spirit of the times” that is daring and evokes emotions.

Secondly, we can catch a glimpse of a territorial projection of architecture that shows attraction for large scale dimensions (both geographical and commercial), and for a certain poetical spirit of of “megalithic structures” that in a short period of time became a rather recurrent composition theme especially in the important tenders for the contracts of the directional centers of Turin (1962) and for the Sacca del Tronchetto in Venice (1964), and that were reintroduced in the history of modern architecture by the famous book by Reiner Bahnam[1].

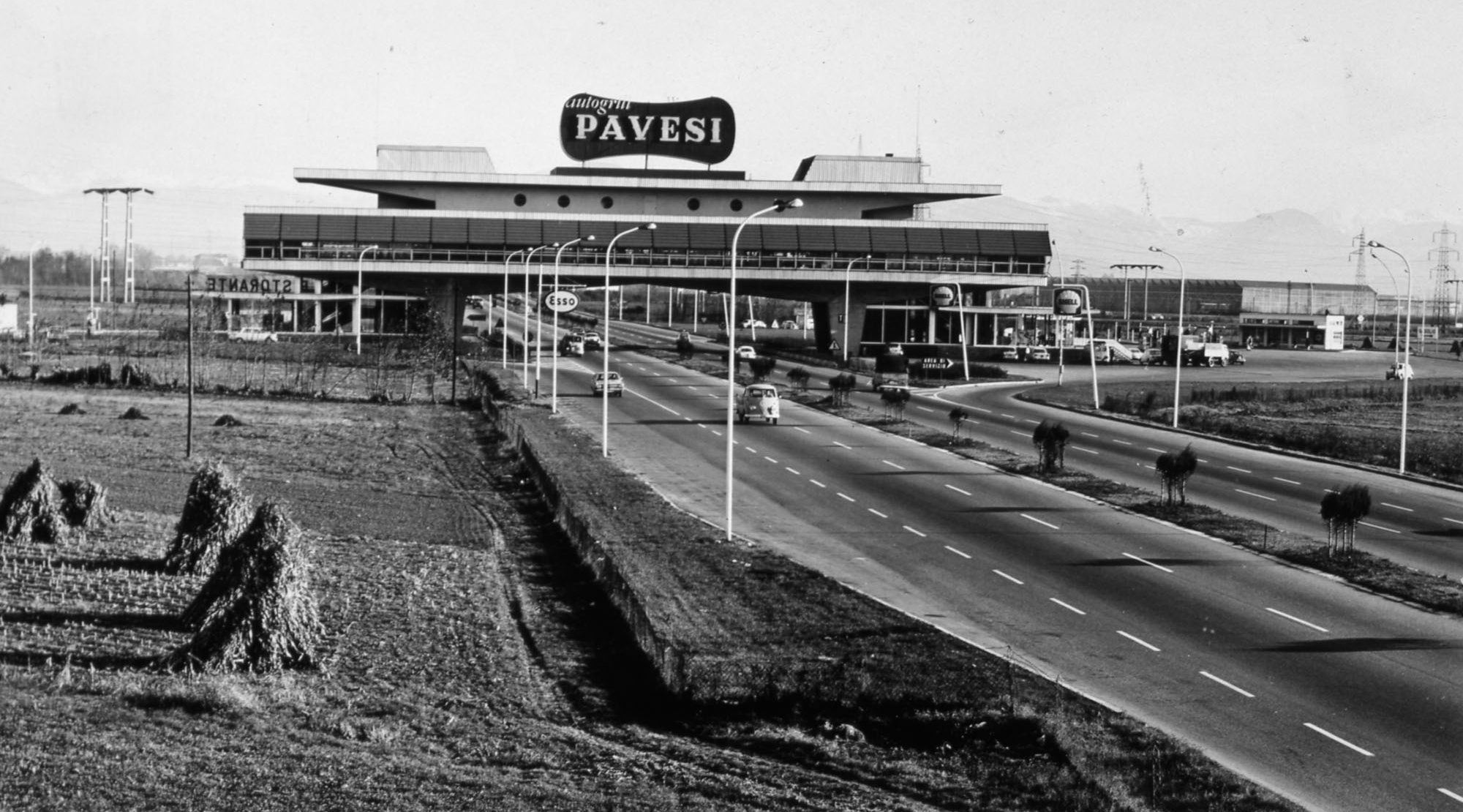

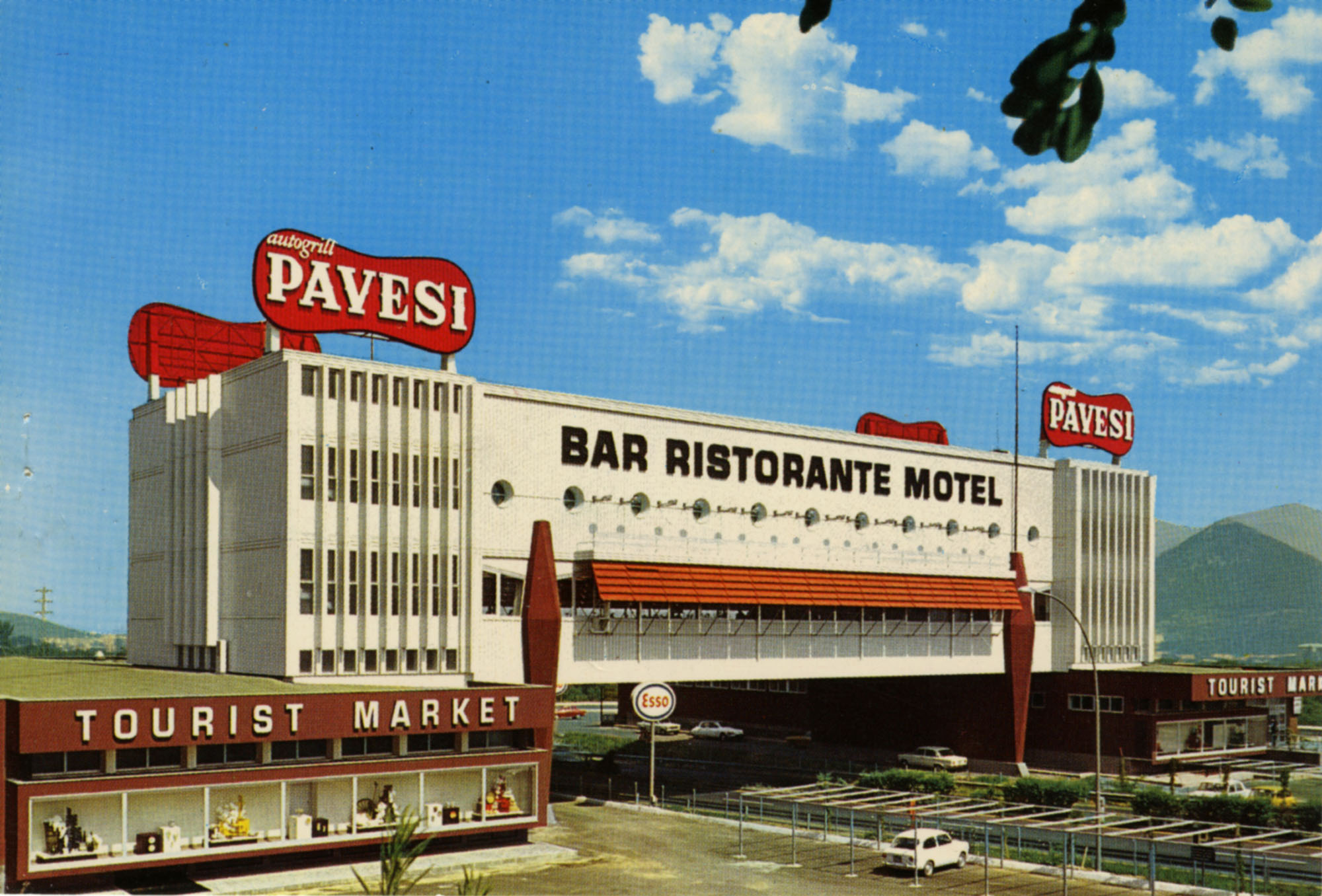

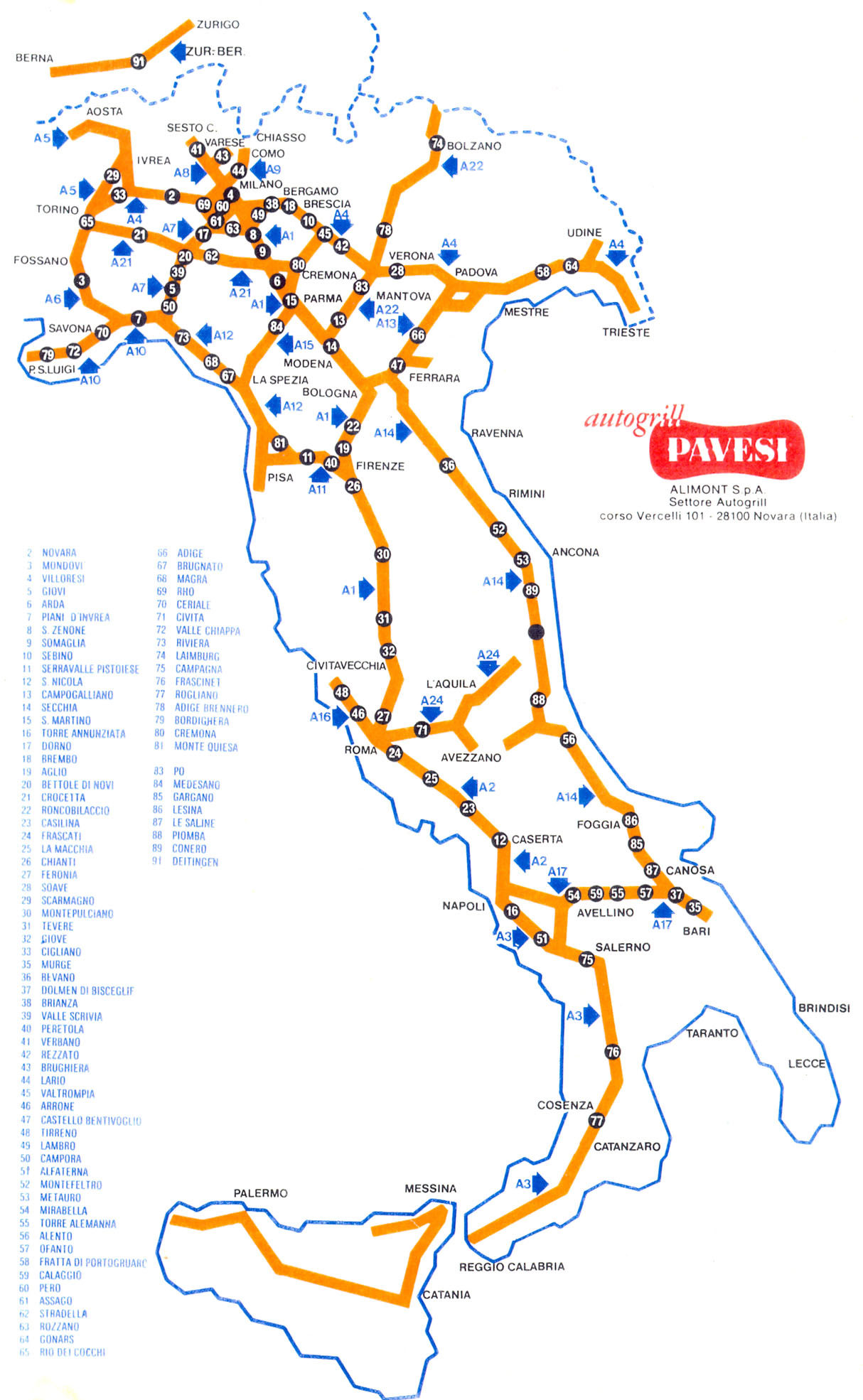

As a phenomenon, the bridge architecture of the Pavesi Autogrills is impressed in the collective memory of the Italian highway landscape even though their construction is circumscribed to about twelve such buildings in the course of about ten years, between 1959 and 1972, in the same period in which the Italian highway system developed.

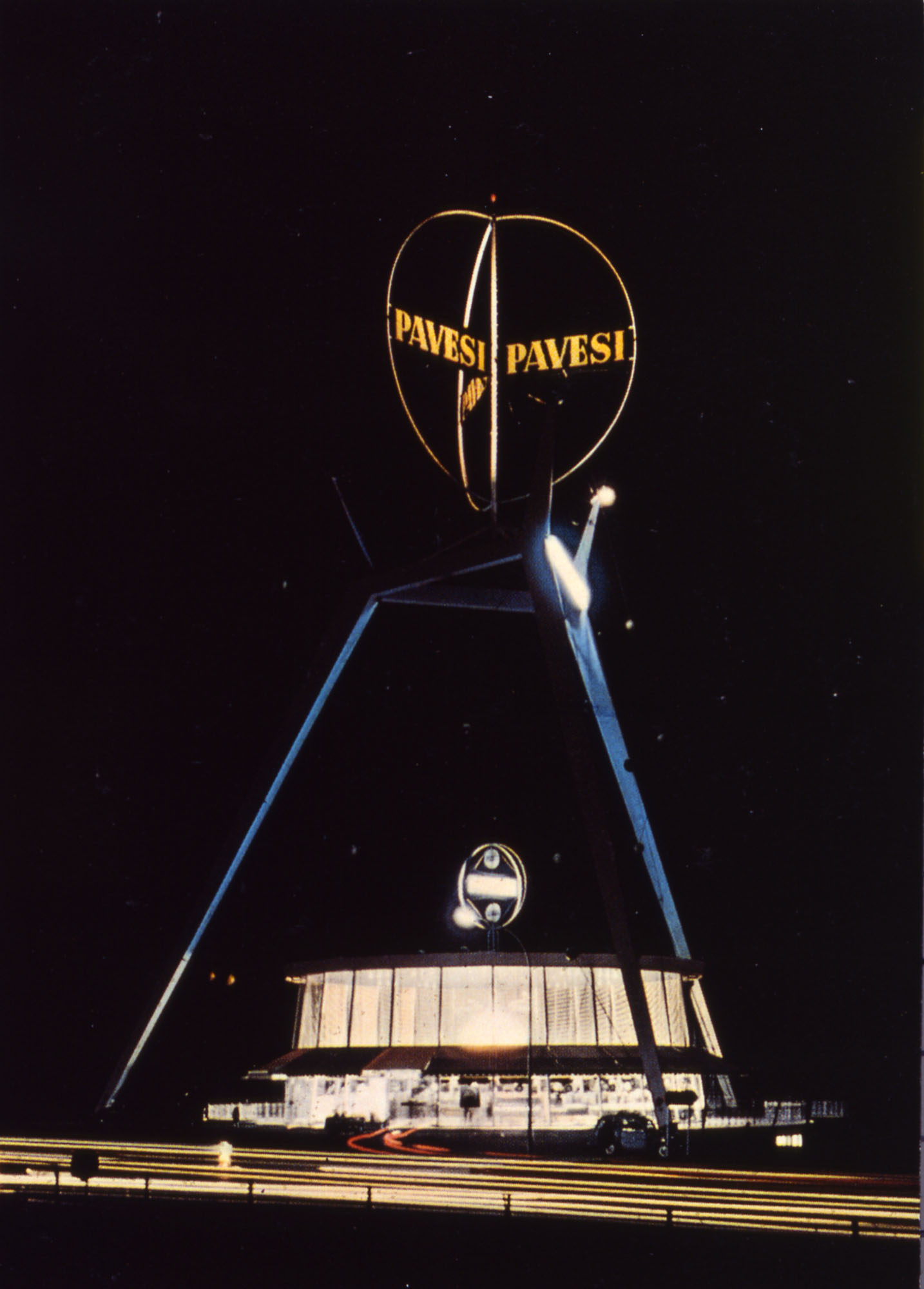

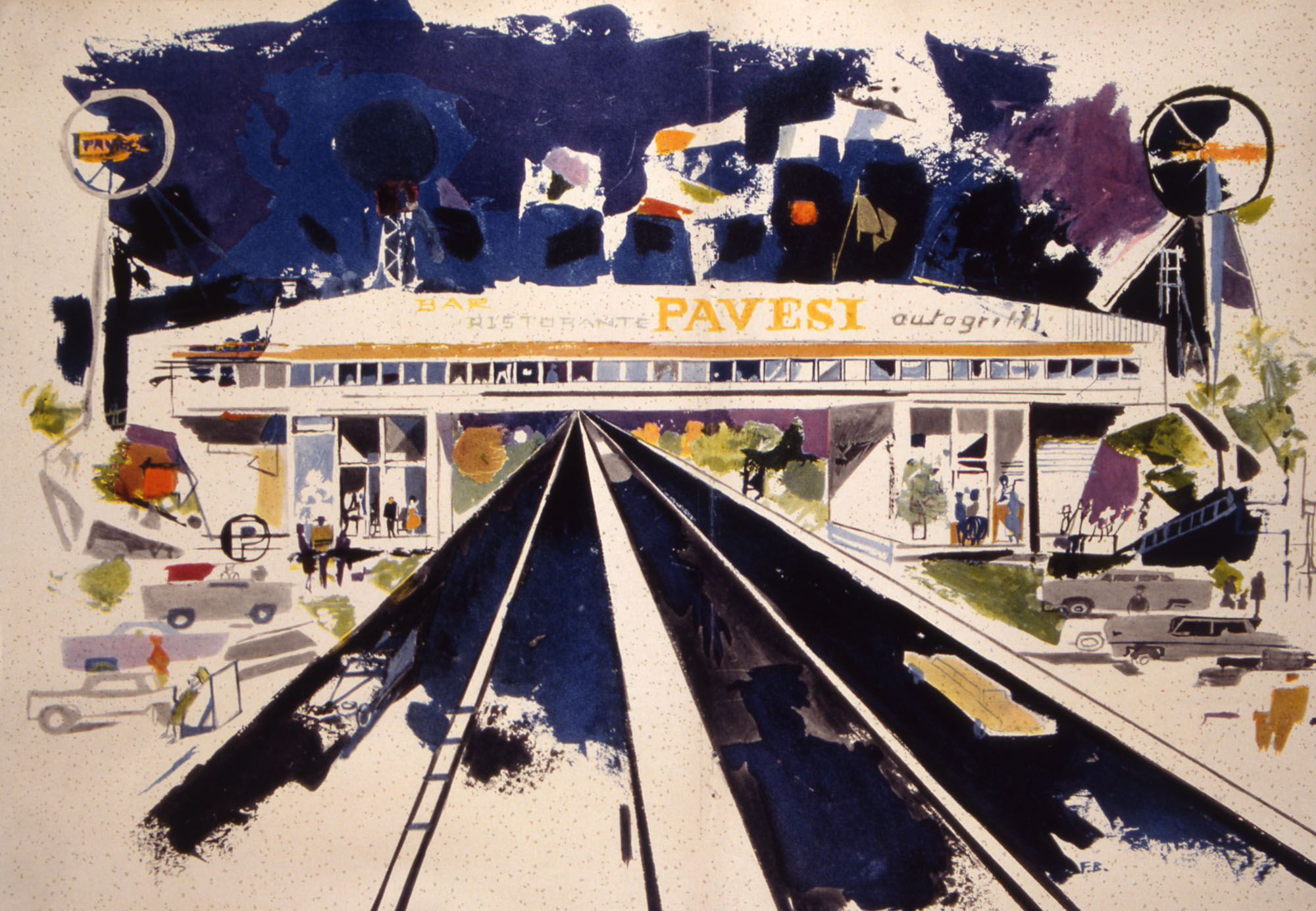

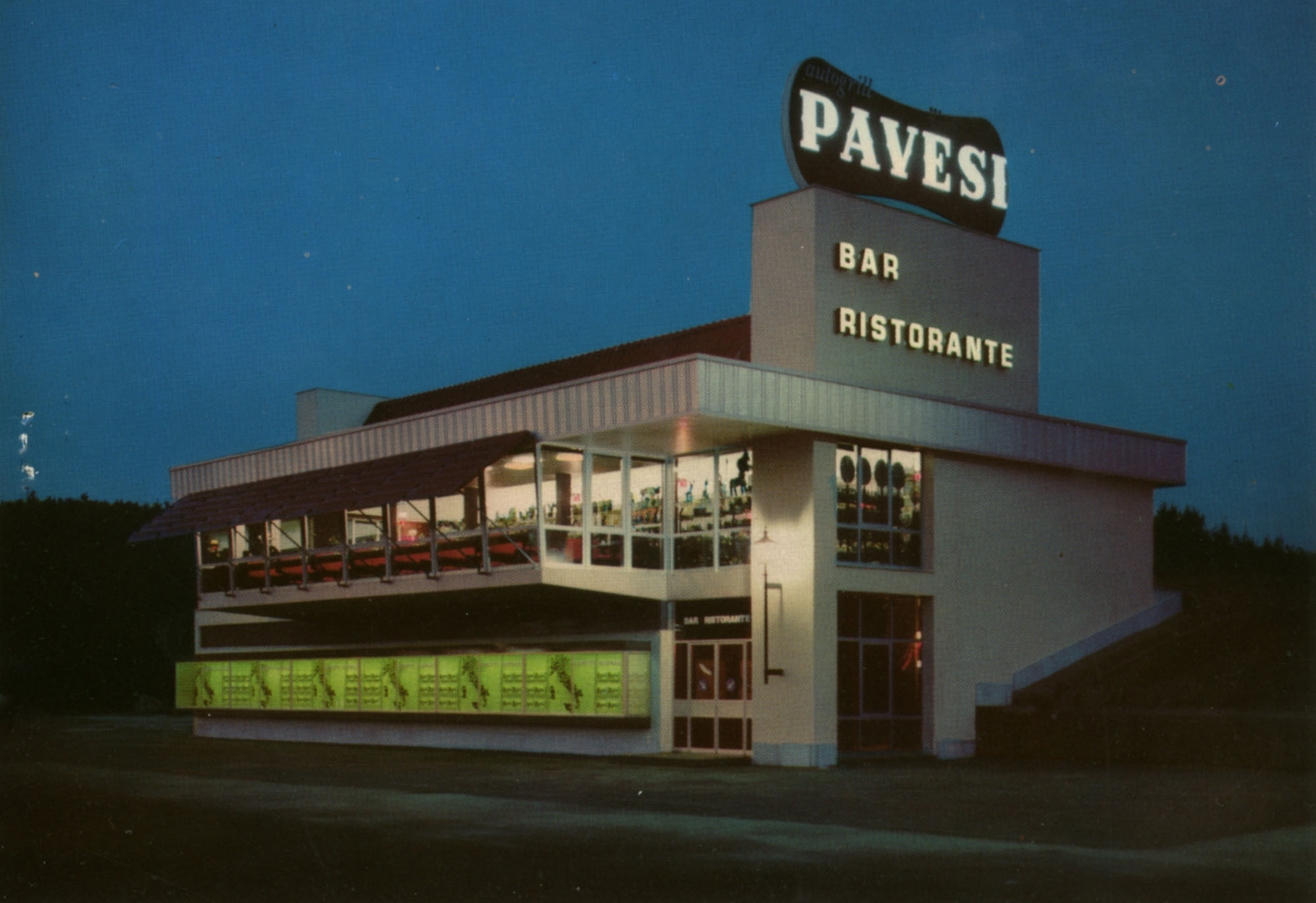

Still today, going through these works of “advertising architecture” that nowadays show subdued colors with respect to the surrounding landscape thanks to a restyling, awakens the attention of hasty travelers that can see the Autogrills arising from a great distance or appearing all of a sudden between a sequence of bridges to disappear in a moment at one’s back, leaving an impression in the memory of crossing something extremely vital, like a fragment of a city. Unusual an beautiful perspectives vertiginously attracted by the dynamic perception of vehicles appeared in the eyes of those who stopped there and sat at the tables facing the highway lanes, especially of the countryside of the Po River Valley.

Because of this fascination with the landscape of a modern territory, the localization of bridged Autogrills did not follow the false ambition of aesthetics in the quest for a setting that could be compatible with the surrounding scenery or that could be particularly persuasive, but on the contrary, these bridges were located strategically on the territory according to a design that was very coherent with a market strategy that was starting to understand that rest areas for car travelers were a new large commercial sector and a channel for the diffusion of novelty food products.

This concept, genuinely based on the market and on novelty foods merchandising, followed a system of modern objects which were strictly connected to a new industrial culture that was developing in those times.

But the real innovation which came was to be that of typology, probably born around a planning table rather than at the design desk by the ideas of architect Bianchetti and entrepreneur Pavesi, and surely in a moment of conjunction between the innovative and open industrial culture ad an architectural culture that even before those times had developed interesting experiences and experimental works through the forms of the Modernist Movement, catching the attention of international culture.

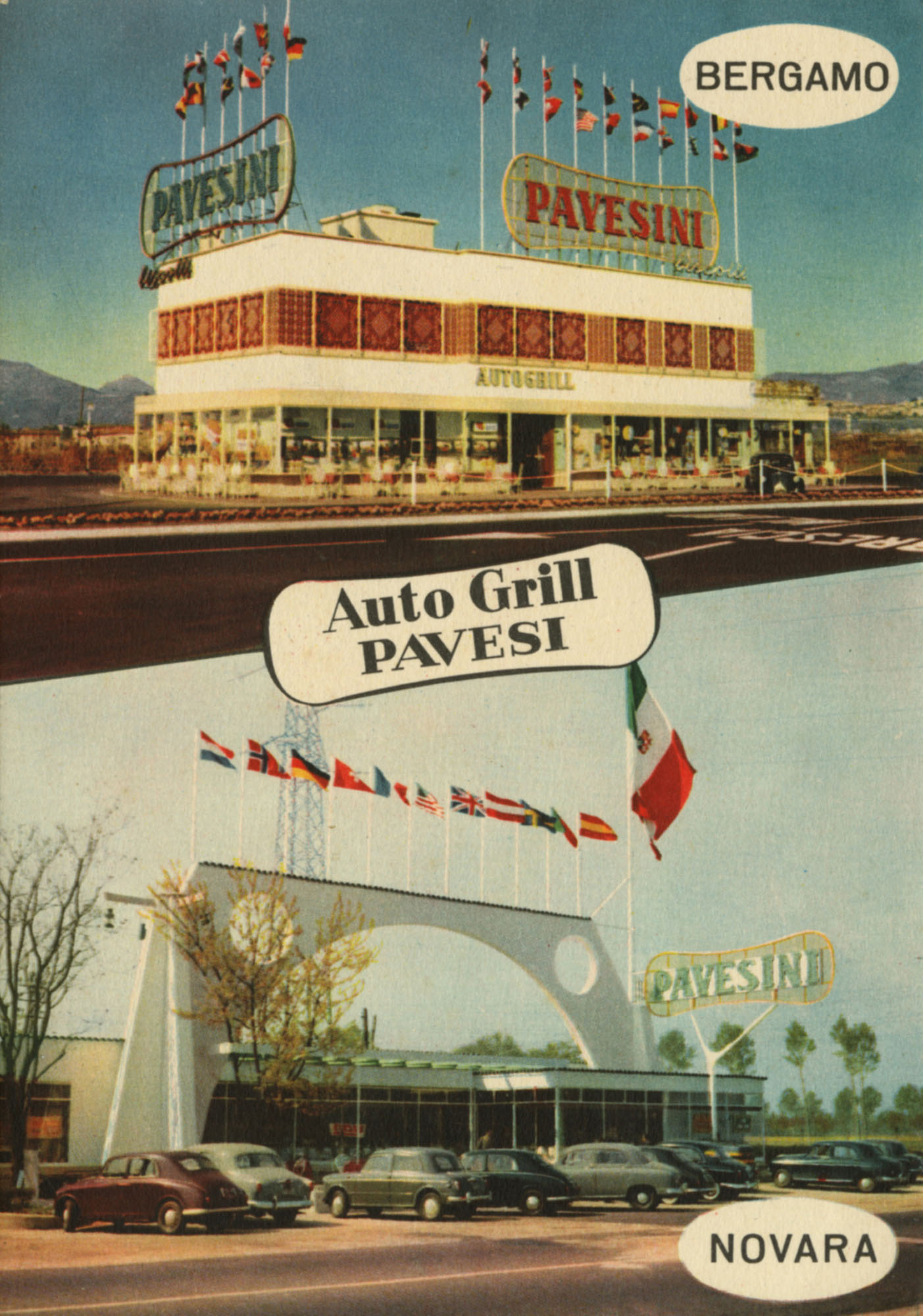

Therfore the diffusion of the Pavesi Autogrills started with the intuition that Mario Pavesi had of a possible market for a chain of highway restoration points, and this became a solid reality with the first rest area in Novara along the stretch of the Turin-Milan highway. This industrial strategy, joined with the forms of advertising architectures by Angelo Bianchetti, made it possible to construct about one hundred restoration points in the span of about twenty years from 1959 to 1978, with about fifty of these being full size Autogrills.

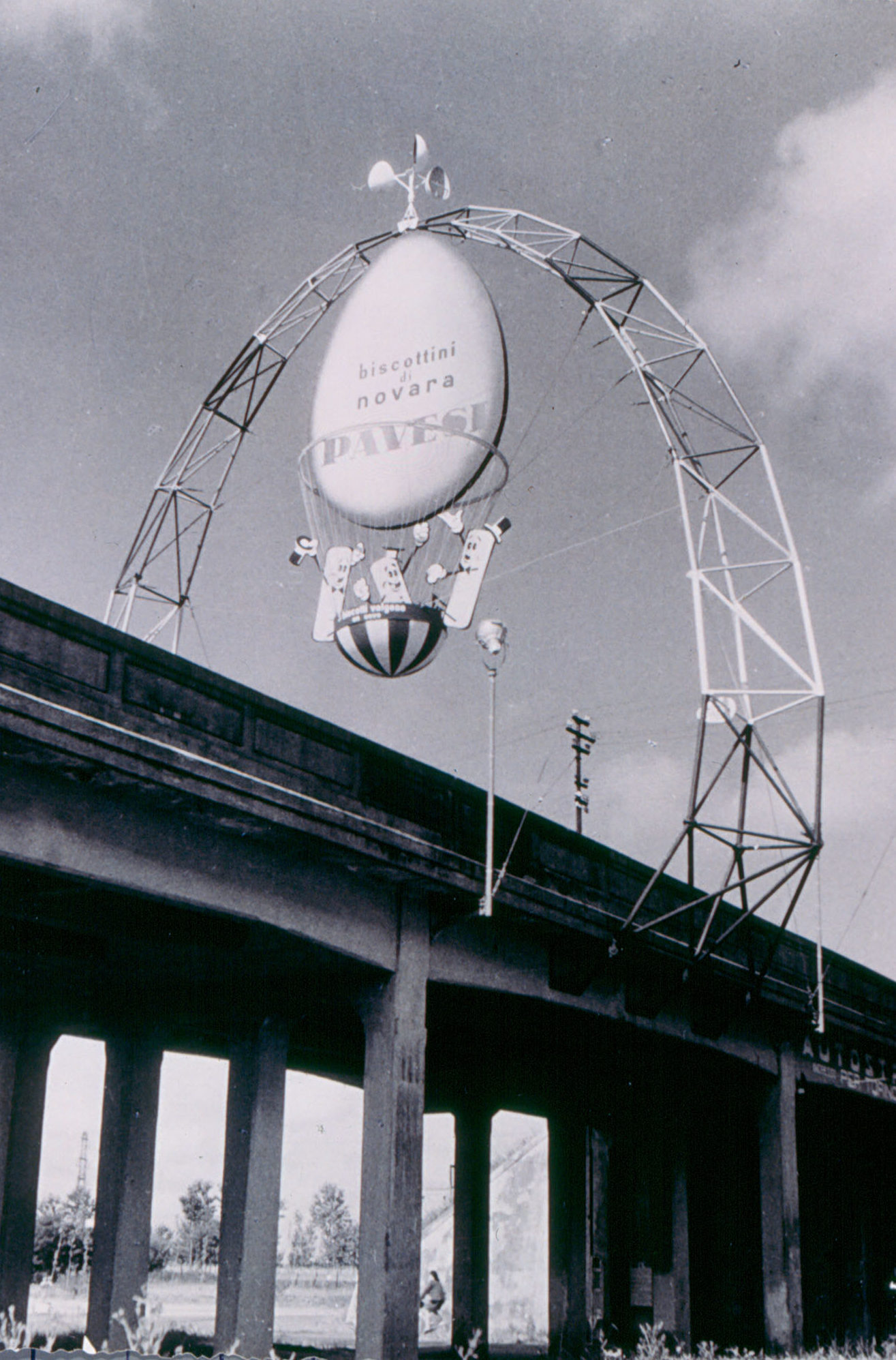

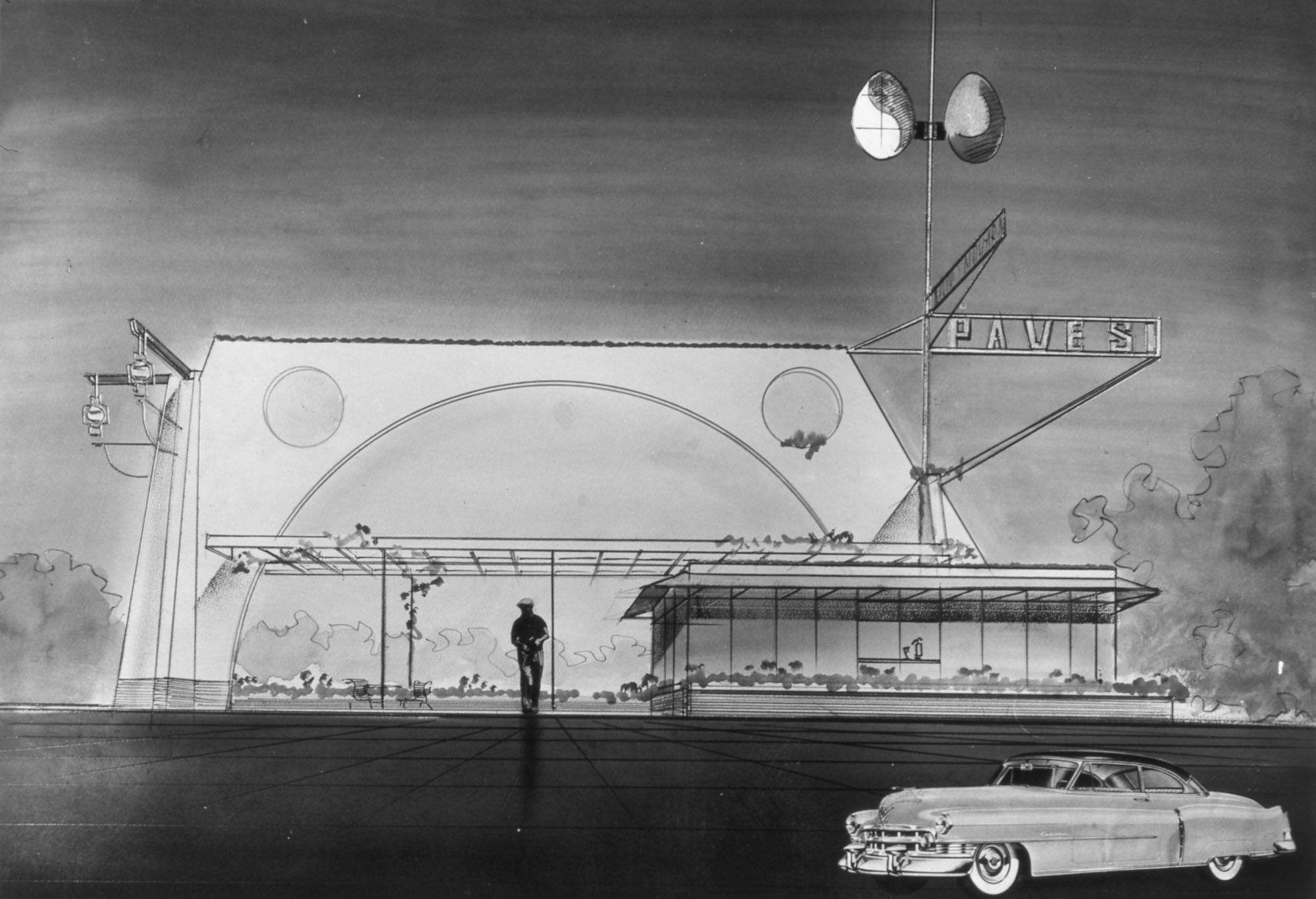

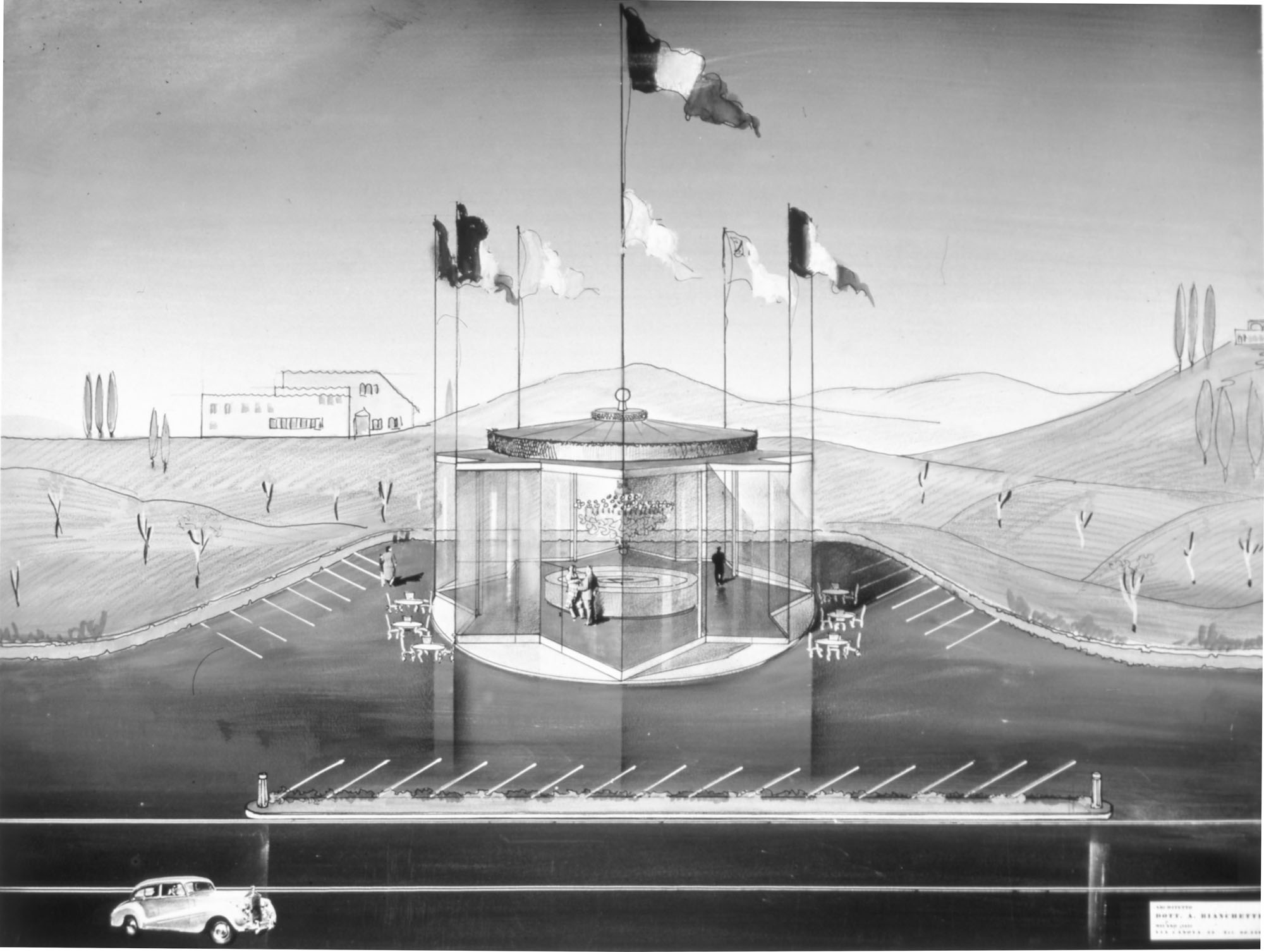

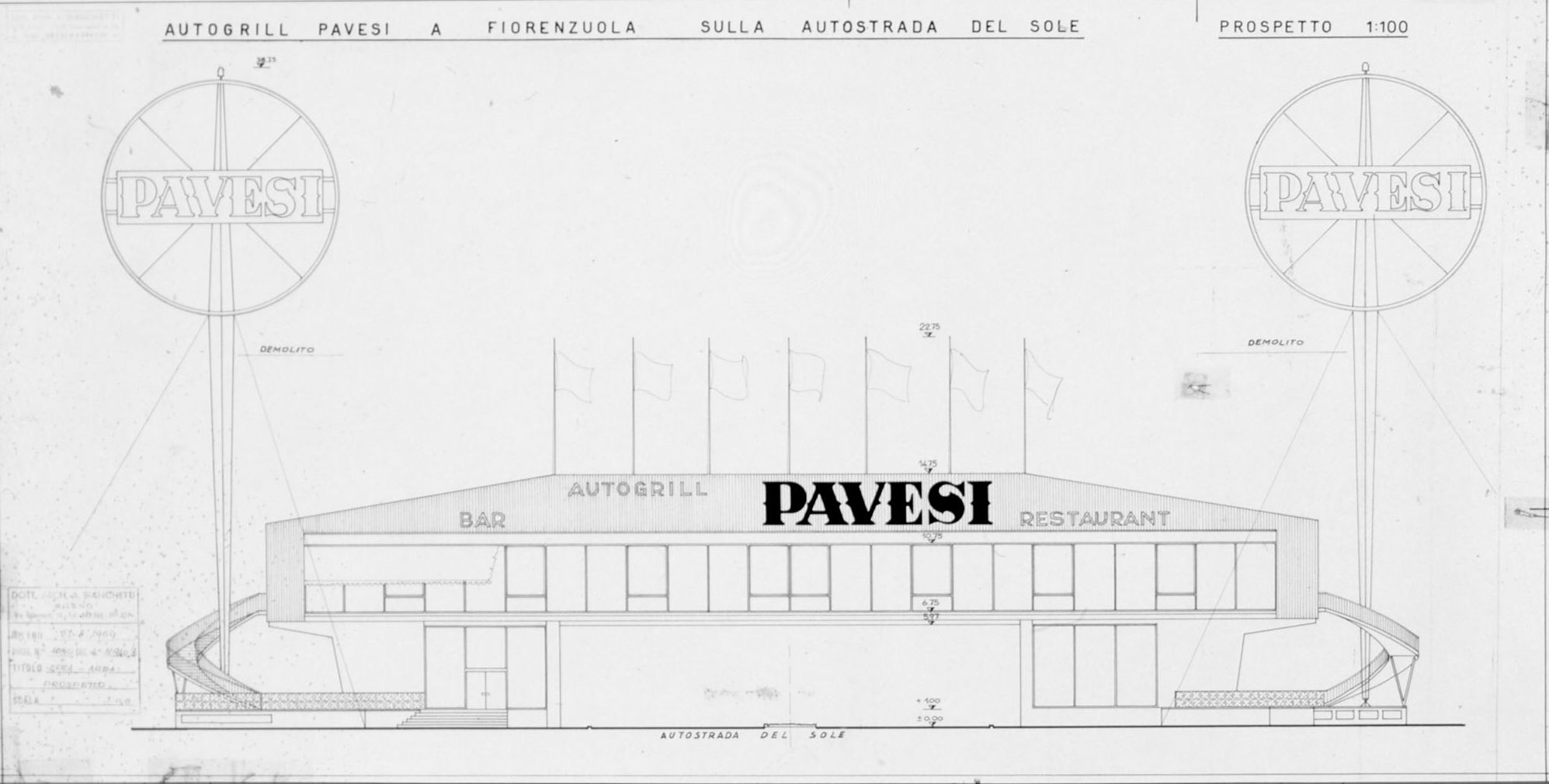

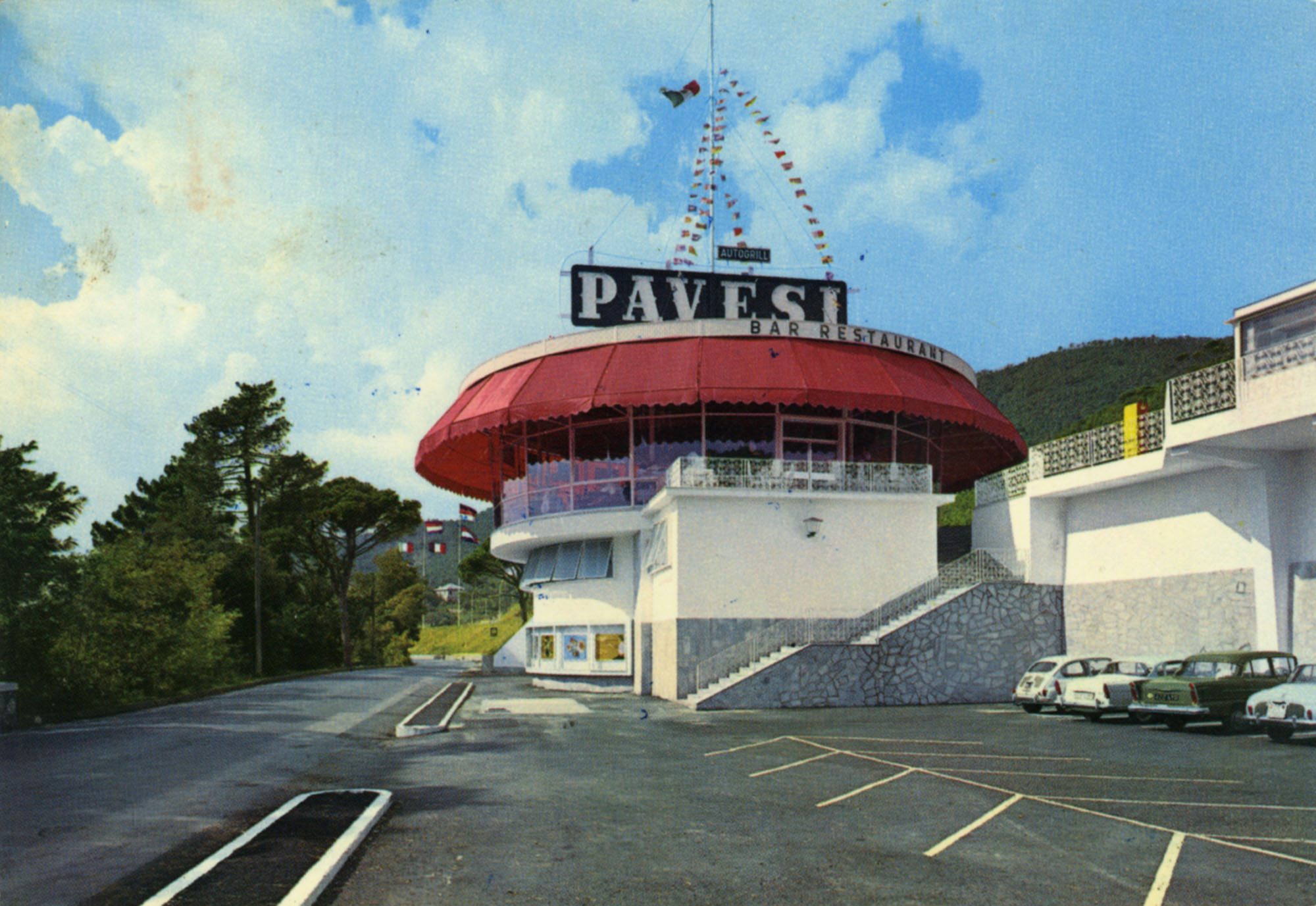

During an initial phase of formal structuring that cannot be precisely indicated by temporal references, the first rest areas were located laterally with respect to the highway in Lainate (Milan, 1958), in Ronco Scrivia (Genoa, 1958), and in Varazze (Genoa, 1960), and featured large steel arches painted in white that supported the logotype and were placed on top of circular transparent structures containing a bar and shelves to sell products. These still followed the architectural matrix of pavilions made for fair exhibits, but with a substantial difference in the fact that their silhouette stood out against the Italian countryside landscape of the time creating a unique and surprising setting. The bridge typology was the evolution of this asymmetrical disposition of rest areas on one side of the highway with an underpass that made them reachable from the other lane. The first example of bridged rest areas for the Pavesi chain (and perhaps the first one in the world), was the rest area of Fiorenzuola d’Arda (Piacenza, December 21, 1959).

Therefore, it seems possible that he phenomenon of the birth and the diffusion of the highway rest areas, especially for what concerns the definition of the bridge typology and for a certain quality of the services offered, originated in Italy. Bianchetti himself attests this in an interesting report of a journey published by the magazine “Quattroruote” (four wheels) in 1960, describing the diffusion of auto-grills areas observed during his travel in the United States and in Germany and comparing it with the Italian situation. In this writing, there is a striking recognition of a contemporary trend in the making of similar structures: Bianchetti illustrates the project of a bridged rest area in Illinois by the Standard Motor Oil chain, and praises the high quality of the environment of the rest areas of the Howard Johnson chain.

«I learned that architects Rinford and Genther are building in Chicago an extremely new design, and I reached them by taking a flight. The two architects work for Pace Associates, a studio of Italian origins, and their first constructions are being completed at a few tens of kilometers from the metropolis: it is a series of five restaurants bars. In general, they look like the ones that will be built on our Autostrada del Sole.

I reached one of these areas that has already been completed at about fifty kilometers from Chicago by car. It is built like a bridge on the highway, with the use of prefabricated cement structures, and the rest area, when seen from a distance, looks like a massive overpass.

At night, with the light reflecting on the walls made of smoothed glass, it gives you the idea of a ship. Once again, prefect signposting and the agile game of “four leaf clover” exits facilitate the passage of clientele: the psychological tests confirm that the decision of stopping does not impose any conscious effort of will on the driver. To avoid the problem of stairs and elevators, the builders even provided to raise the entire area of parking lots and platforms. You can reach the level of the “restaurant floor” by car. But how much will one of these colossal structures cost, without considering the cost of parking lots, of lanes, signposting and many more indispensable accessory expenses?

The two architects informed me that the average expense is of about one billion Italian Lire. The surprising kitchen tools made of stainless steel that you can find in detailed description in a book of three hundred pages cost a little less of two hundred million Lire alone. It is a real treatise»[2].

Among the bridged Autogrills that followed shortly after this period, we find the Abraham Lincoln Oasis by David Haid on the Northern Illinois Highway of circa 1967, with its elegant and minimal geometries of steel beams and glass and with its use of the criteria of access ramps to parking lots to reach the restaurant level. In Italy, we must take note of some bridged rest areas of the Motta chain in Cantagallo by Melchiorre Bega, and in Limena by Pier Luigi Nervi.

In any case, the construction of bridged Autogrills increased the possibilities of access, but their limitations in the possible increase of utility ad renewal seemed perhaps too binding and costly in the massive increase in highway traffic of the 1980s, determining the actual exhaustion of possibilities for this extremely interesting typology, as Angelo Bianchetti himself at the time recalled in one of his short writings of 1979, underlining a paradoxical situation of inadequacy to the market in a climate of full economic recession and energetic crises.

«[…] the cost of a bridge with all of its accessories was clearly lower than that of two lateral Autogrills, without mentioning that noteworthy savings on operating costs, both for the installation and for the personnel. The visibility at a distance is much more immediate of that which a later Autogrill offers: let us not forget that a driver traveling at a speed of 120—140 kilometer per hour must decide in a few seconds whether to enter or not the ramp of deceleration.

In conclusion, the advertising image of a bridge is by itself more effective and of sure appeal. […]. Today the situation has changed. The huge increase of costs (fuels, cost of operating machines) has slowed down the flow of traffic and has reduced the user’s spending possibilities.

The cost of construction with respect to 1972 is almost fourfold, and it has increased terribly. All this imposes a revision of the investment policies; the tendency today is not to build new Autogrills but at the most new snack-bars connected to a nearby gas station. It not feasible anymore to build a bridge, unless in an extremely well established service area of large traffic that can guarantee the constant flow and support of travelers»[3].

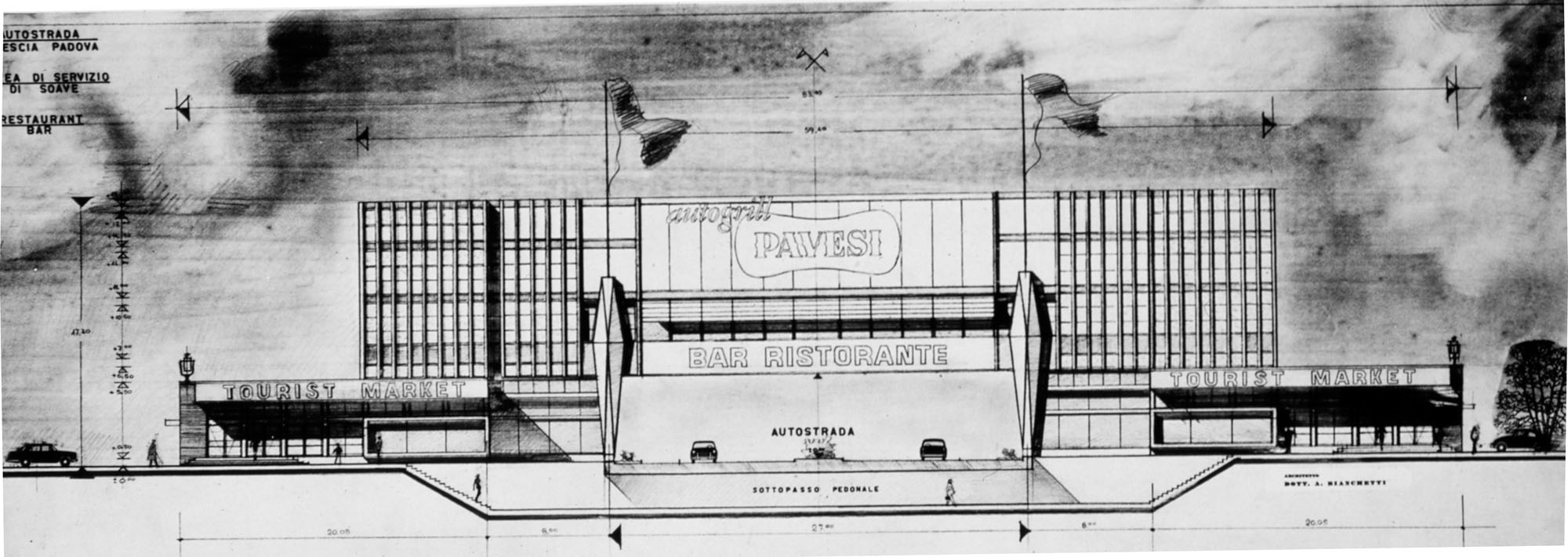

The numerous formal variation of these bridge installation extended the possibilities for signposting through flagpoles dressed up with the Pavesi flags like ships on a dock, or through some functional increases, like the annexation of a motel. The one in Novara (1962), that replaced a previous service station and that was the largest one built, and the one in Osio (Bergamo 1972), the last to be built with bridge typology, were identical in lines and shapes and were perhaps the most successful ones, while the one in Montepulciano (Siena, 1967) features an extremely striking and apparently suspended beaming and a projection of Corten steel. Lastly; the one in Nocera (Salerno, 1971), presents an interesting combination with the function of motel, attempted as an enlargement project in the one in Novara as well, but then never built. The other bridged ones are in Sebino (Brescia, 1962), Feronia (Rome, 1964), Frascati (Rome, 1963), Soave (Verona, 1969), Rezzato Nord (Brescia, 1970).

Nonetheless some characteristics remained a constant, like a certain formal uniqueness and sense of completion of the construction that gave a full rounded perception of the buildings even in the headboards frequently crowned by a large cantilever staircase. This can be seen clearly in period photos and it is less noticeable nowadays because of the frequent addition of low lateral tourist market buildings and because of softer colors used. The chromatic treatment of the metal sun shading roofs (a bright red color) became the distinctive feature of Pavesi Autogrills and circumscribed the building itself in the whole, while the balanced collocation of the few billboards did not enter into conflict with the gasoline signposts but on the contrary seemed to match them, and at night these were lit by their own lights. Moreover some gasoline stations designed by Bianchetti like the one in Sabino for Esso, distinguished themselves for the essential nature and elegance of structures with tall and slender signs and prismatic elements for the buildings.

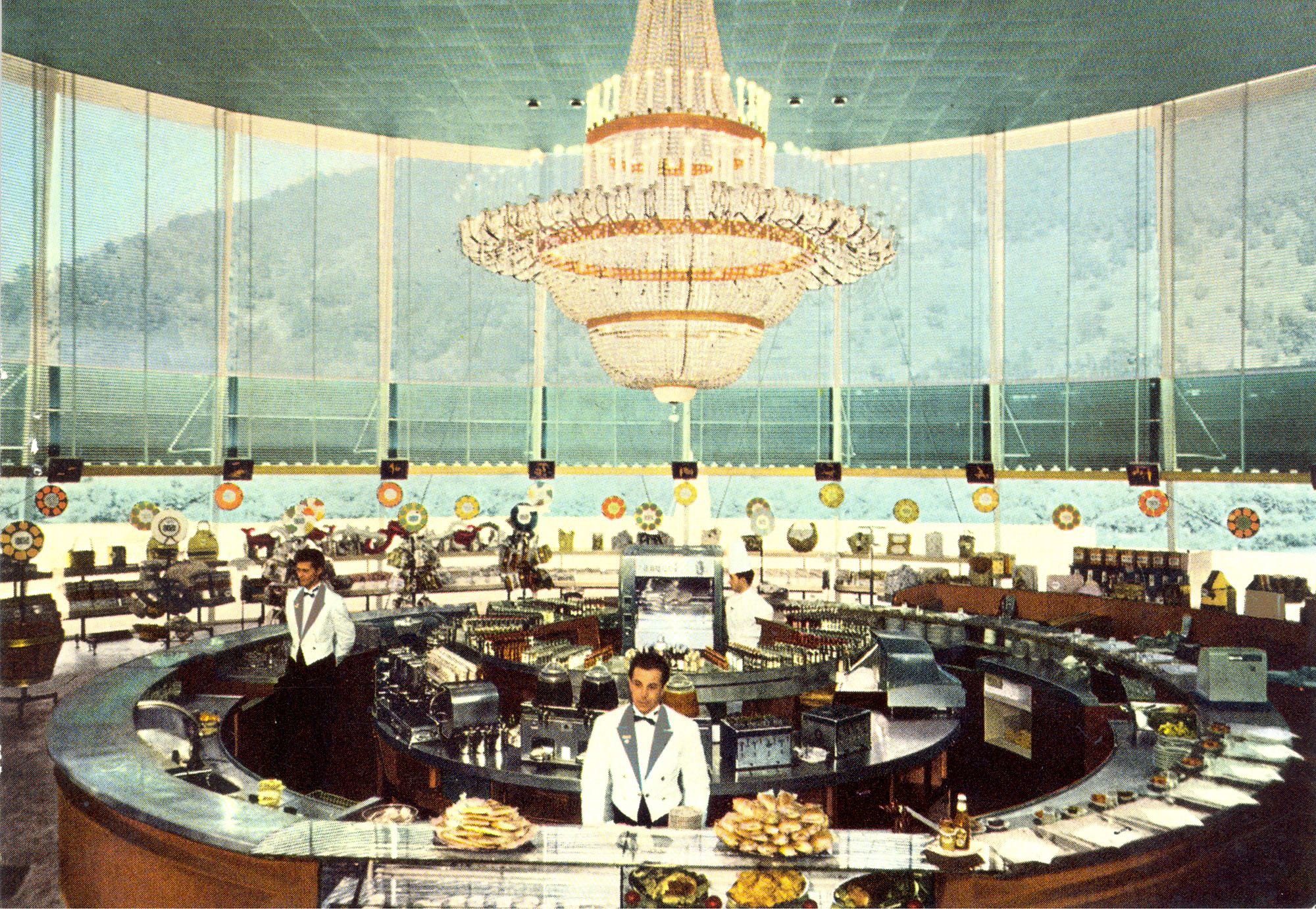

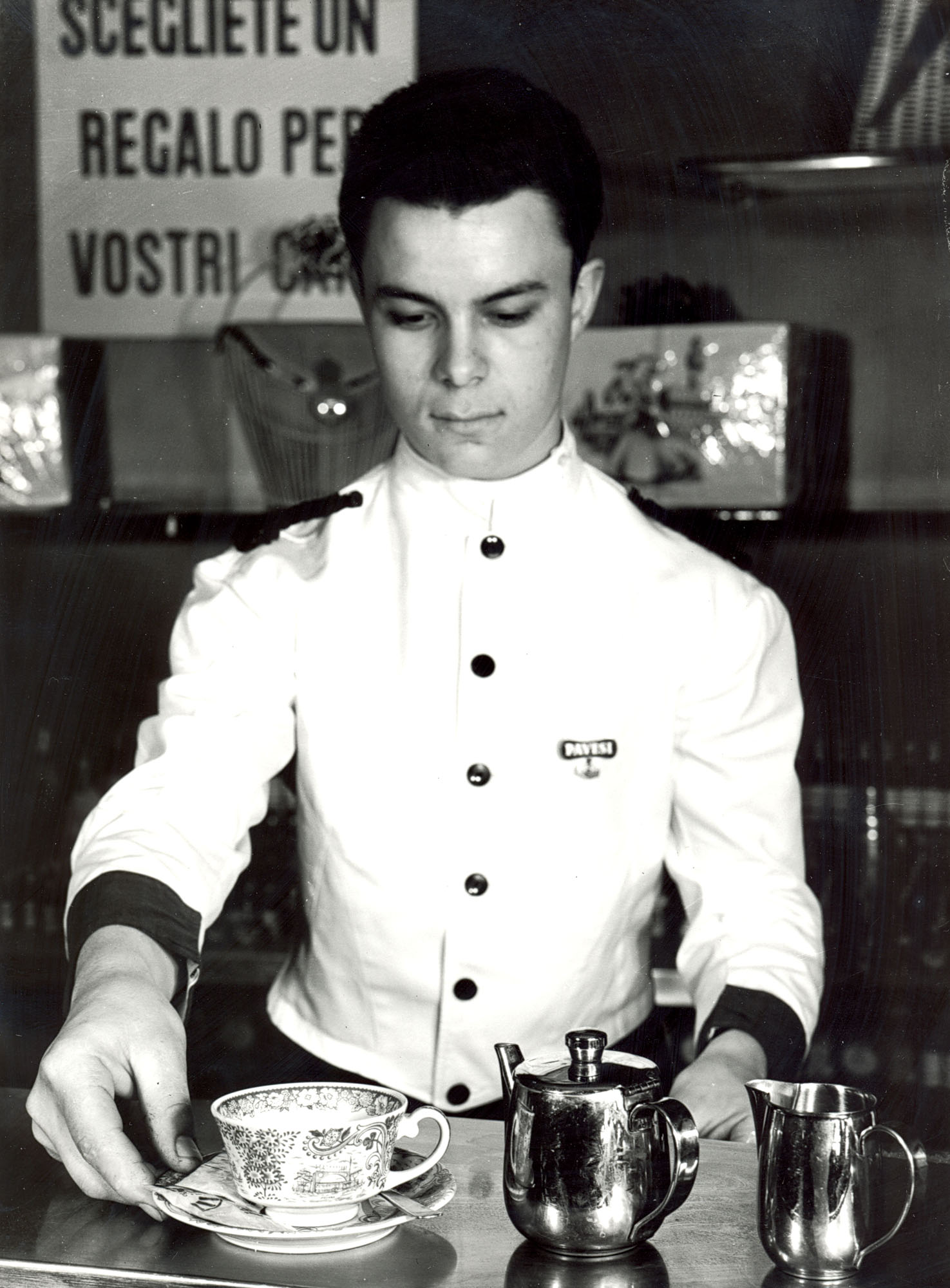

The inside was indeed surprising for the type of light that filtered as a reflection and for the continuous perception of the dimension of inner space as a whole due to a longitudinal disposition of the counters and to the a contined set up of the product shelving, evoking a perception of the Autogrill as a self standing unit animated by its own life in the multiplicity of people that entered there.

The setting implied a reduction of the strictly communicative aspects to the simple interior design of the space, with a playful sense in the disenchanted and free style collage of Baroque and modern elements like the large glass drops chandelier in Lainate that appeared on the pages of “Life” magazine, or the Vietri ceramic tiles flooring frequently utilized, or the woven wicker baskets used as displays for the Pavesi products, to the concise inner signs that retraced the highway signs and to the essential lines of the American style counters with stools. It was anything but a coordinated image, but in the end it was a greatly coherent setting with regard to expressiveness, and it was handled case by case solely through the architecture, without any apparent preoccupation with the integration of aesthetics except perhaps the idea of a vanguard collage that actually was a trend in the taste in advertising graphic art of those years (especially for Erberto Carboni) and that had its origin in the experiments in modern architecture made between the two wars, as we will shortly see.

Lastly, a third typology of construction contemporary with the bridged one was a design foreseeing a restaurant area lateral to the highway with a red sheet metal covering with four layers which was much more flexible in adapting to dimensions.

Alongside with the wide diffusion of Pavesi Autogrills (Alivar- Pavesi), Motta Autogrill and Alemagna Autobar (ex-Unidal) chains developed in Italy, and then were ex-corporate from their respective head companies on February 28, 1977 and regrouped in to the Autogrill spa society that today manages all of the restoration points along the highway.

The experimental tradition of “advertising architecture”

The experiences made by Angelo Bianchetti (born in 1911 and died in 1995) before World War II are extremely interesting and represent an very significant anterior fact to understand the reasons that brought to the long collaboration with Pavesi. A graduate in Architecture of the Milan Polytechnic in 1934, he traveled to study in Germany, worked in Berlin for the Mies van del Rohe studio and for the Luckard brothers studio, and met Gropius and Breuer.

In Italy, he worked with Giuseppe Pagano on a few projects in 1938 thus completing an itinerary that crossed the most significant episodes of modern architecture of our century, following a tradition of international exchanges that at the time was widely spread. As a project designer, often together with Cesare Pea, he worked on a number of architectural layouts for exhibits and advertising pavilions for fairs, and became one of the main protagonists of a theme of construction that back then was completely new – the theme of exhibit architecture, a culturally important and acknowledged theme in the landscape of modern international architecture.

This was a theme on which the most important architects, graphic designers and artists of the cultural Italian scene between the two wars had a lively debate, especially during the era of Fascism, that saw in it a real modernity of communication and a dose of inventive ruthlessness and cultural availability together with the ability to give the large industrial groups occasions to promote their modern and cosmopolitan image (though a dictatorial one) in Italy and abroad through important international expos.

Therefore, modern Italian architecture in those years was able to channel the needs of propaganda within the paths of a history of art and within those plastic and figurative values that were more attentive to moral issues. In this sense, the possibilities for formal experimentation that architecture made possible back then established a few solid principles of an Italian rationalistic poetical style that was intended as expression of a lyricism and that had no equal in later years.

The “Casabella -Costruzioni” magazine directed by Giuseppe Pagano, reported on numerous occasions the main exhibits made in the heroic period that goes from 1925 to 1940 in which Angelo Bianchetti took part as the author of beautiful set ups together with other important emerging names like Erberto Carboni, Marcello Nizzoli, Bruno Munari,t the Boggeri studio (that in the years following the war we will find working for Barilla, Olivetti, Agip, …).

Of these exhibit set ups, we must mention the pavilions by Edoardo Persico and Marcello Nizzoli for the Italian Aeronautical Expo of Milan in 1934; the Gio Ponti and Erberto Carboni pavilions for the Exhibit of Catholic Press at the Vatican in 1935; the set up of the Hall of Victory at the VI Triennial Expo of Milan of 1936 by Nizzoli, Palanti, Persico, Fontana (in those times already referred to as “a work of rare and highest poetry”); the Italian pavilions for the Paris Expo of 1937 with the intervention of the most important Italian architects; the pavilion by Bianchetti and Pea and the Boggeri Studio for the Isotta Fraschini company at the Fair of Milan in 1938; the luminous surface tensions by Nizzoli and Bianchetti at the National Textiles Exhibit in Rome in 1939; the Bianchetti and Pea pavilions for Raion and for Chatillon at the Milan Fair of 1939, formed by a lightweight frame with three orders and covered by light ad small vaults shaped like a transparent and lyrical honor tribune in the way that only Italian Rationalism was able to do.

These operations for temporary set ups connected the languages of abstraction and of the pure forms of international Realism with a Baroque vein expressed in the combination of graphic and sculptural elements, in the use of curtains and of narrative naturalistic elements (from the sculpture by Fontana for the Hall of Victory at the Triennial Expo of 1936 to the advertising signs of the textiles pavilion, according to a poetic and rather unique idea of collage that was very original in the landscape of modern architecture.

Very important in order to comprehend the pragmatic spirit of this theme for the architectural modern culture of those times is a writing by Angelo Bianchetti and Cesare Pea of 1941 on the theme of advertising architecture that establishes some characteristics that were undoubtedly reprised in the exhibit architecture of the years after the war and that created the premise for the Italian highway landscape of advertising architecture.

First of all, what is striking about this writing is the concept that these architectures can serve the function of contributing in a positive way to the definition of a new urban landscape already projected towards the torments of an undefined territory structured with fair headquarters and sport centers, theme parks, shopping centers and highway congestion points, starting from the occasion of an advertising set up intended in architectural terms.

Secondly, these constructions are not just inserted in a system of means of transportation to guarantee elevated accessibility, but also to accentuate the dynamic perception of the whole, and in this sense the relationship between bridged Autogrills and the highway exalts the aesthetics of kinematics.

In third place, it is striking that architecture partially renounced some building aspects to rediscover the values and new aesthetic concept of monument through a combination of signposting, graphic, and visual communication that penetrates indoors, in the furnishings, and recomposes a unity of applied arts.

«Le Corbusier and M. Breuer build their advertising architectures on the base of their artistic abilities more that to their architectural skills. An active pictorial imagination gives the project designer the possibility to renounce to give an entirely constructional and formally still aspect to his own pavilion. We think that this can be conceived in such a way to appear based on a single structure with the use of substantially different solutions. The ideal pavilion from the advertising point of view is one composed of fixed elements related to the laws of building statics that at the same time offer to the imagination different possibilities of a practical nature, that can be made also in successive phases. Therefore, not a facade defined architecturally, even though beautiful, but a system of elements and fields in which to express the imaginative spirit of the decorator. In such a way the abilities of a good architect and interior designer can fully develop: the study of the structure will bring him to intuitions of rational architectural order, while the expressive possibility will lead him to use these elements with the highest freedom and to create works of pure artistic design.

The appeal of the suggestive elements that advertising work must express will come from the fusion of these two possibilities. All which modern technique gives the artist as a support, the new materials, new systems of lighting, the cinematographic aspects, the mechanical devices, can concur to the perfection and complexity of the work that the artist conceived with his own imagination. But the use of these elements is part of the generic knowledge of an architect that are not the object of this study.

Instead, the problem that originates from the combination of various pavilions and advertising elements of a Fair or Exhibition forms a chapter of advertising urban planning whose direction would deserve an in depth study»[4].

Architecture and the design of new industrial products in Italy after World War II

The concept of industrial and market that arose in the years after WWII in Italy and throughout all of the 1950s and 1960s can be definitely found in the geographical area between Milan and Turin, the area of the initial development of the highway system, and of the modern democratic entrepreneurial cosmopolitan and culturally engaged world of Olivetti, and of Pavesi of Novara.

It is not a chane that the magazine “Comunità” (community) founded by Adriano Olivetti was engaged in those years in themes of architecture and urban planning and also with sociology in its different aspects of urban development, mass behavior, industrial production, and published studies on advertising and the unconscious mind on the organization of Shopping Centers in the United States, on the Italian highway landscape, or on food consumption in Italy[5].

These themes surfaced with full force in the concerns of the Italian entrepreneurs that frequented the most densely industrialized areas of the United States (especially the West Coast) and in a certain sense these were ideas that could be actualized in Italy as well at least in the smartest industrial sectors that were capable to invest in development.

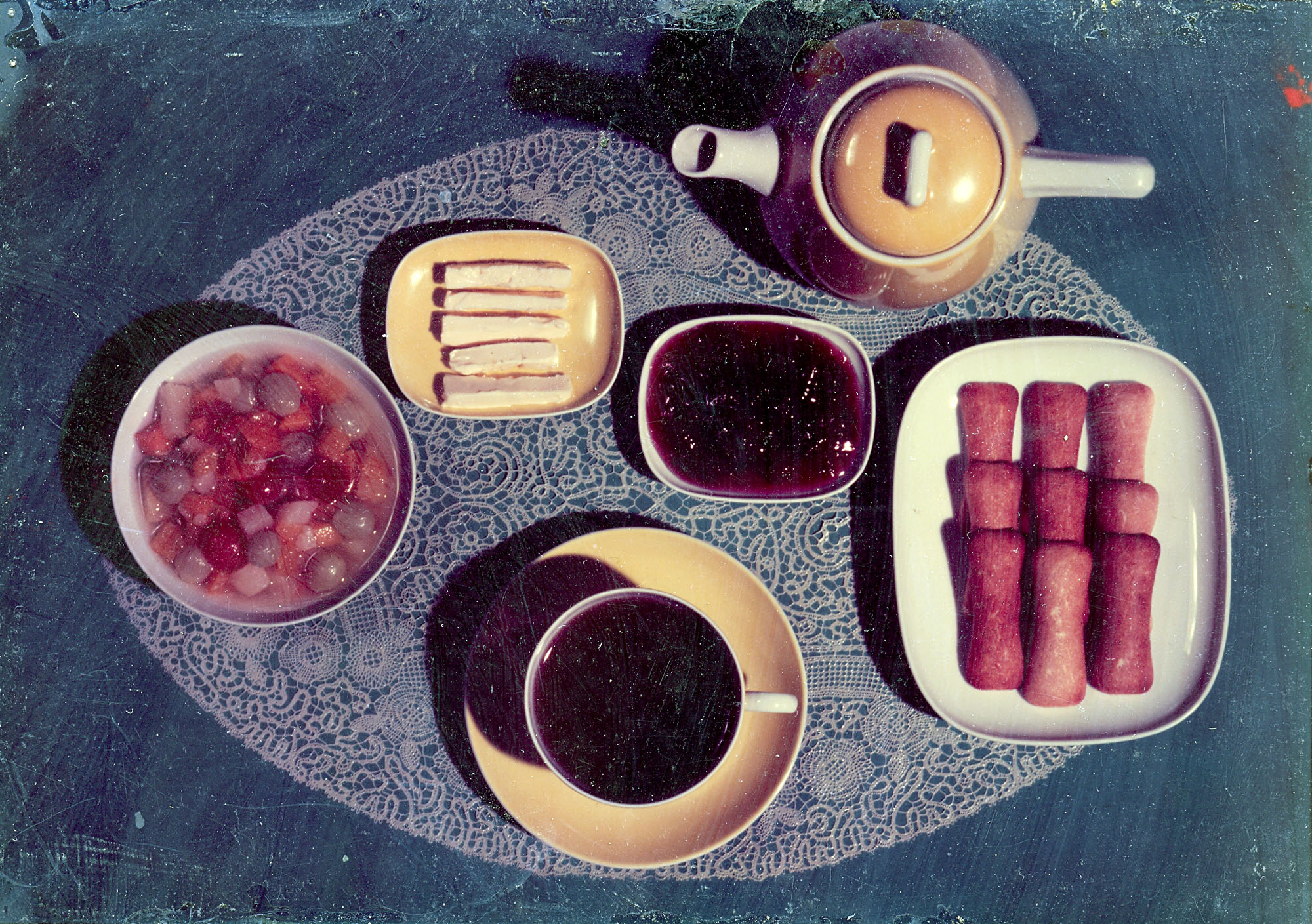

This is certainly the economic context in which the construction of the Pavesi Autogrills was inserted. The idea of modern times and social well being that pervaded the aesthetics of Pavesi Autogrills was based on a completely new food product, the Pavesini cookies and the Crakers, produced on a large industrial scale as never before, and tied to lifestyles and psychologies of use that for the first time in those years surfaced and of which there was full awareness.

But because of the structure of Italian cities, in which the residential Ina-Casa neighborhoods typical of the intensive urban growth of the northern cities tended towards a landscape that was still close to that of a compact city, the shopping centers of the time were of a typology of sales too radical to be proposed, while the Autogrills located on the highways cold well enough be interpreted in this sense as a sales point for novelty industrial products diffused on the territory, in which the market strategies could be applied directly without intermediaries and a modern and cosmopolitan image could be promoted.

The relationship of entrepreneurship and architectural design between Mario Pavesi and Angelo Bianchetti, as well as the relationship with other intellectuals for other more literary and clearly marked graphic forms of communication should not be intended as a cultured construction of corporate identity, nowadays necessarily corresponding to a quote of production that each industrial activity must possess, but as something more complex and with roots going deep into a specific ability of the Italian industrial culture (that with the refined work of Adriano Olivetti reached its apex) to use as its own the tools of communication in the system of behaviors of producers and consumers.

Therefore here it is not solely a matter of refined design of of stylized image but rather of the fine tuning of tools strictly connected to the production and distribution of products, tools in which the aesthetically implications had a place of relevance. A rather significant parallelism involving architecture in the processes of industrial communication happened in the United States at the same time, in the 1950s and 1960s, as the top industries of the time like IBM or the TWA aerial transportation company, for example, asked innovative architects like Charles Eames (who mounted elaborate films and avant-garde multi-vision materials), or Eero Saarinen (who made phantasmagorical theaters for the international expo and to animate the horizons of airports with forms made of cement or crystal and evoking emotions)[6].

These companies entrusted them by delegating the task of building the company image according to a culture of conquest of the new that we still find nowadays, but acted in a different environment, more determined and structured in an entrepreneurial way and in which the need for aesthetics of the object of use was less of a priority, for example, even though often reached results of the highest quality.

But in Italy everything was different: for example, the design by Marcello Nizzoli for a calculator, or the one by Carlo Scarpa for an Olivetti store, or the one by Erberto Carboni for Barilla pasta, or the advertisement for Pavesi cookies written by Gianni Rodari as children literature, were necessary elements of a new concept of the object of use an the work of intellectuals in this context was instrumental to the comprehension of the new industrial products in a domestic and working landscape that was still formed in part by handcrafted objects (and still today attracted strongly by the components of originality and personality also in the aesthetic choice).

Who in Italy would have bought Pavesi, Barilla, and Olivetti products, for example, if a group of food intellectuals had not converted the packaging for food and machines into a new culture of merchandise?

Bibliography note

We thank for his patience and collaboration architect Jan Jacopo Bianchetti who keeps the archive of Angelo Bianchetti’s work and has given permission for the reproduction of the photographic material, the designs and the publications related to the Pavesi Autogrills.

Among the writings of Angelo Bianchetti we mention: Bianchetti, C. Pea, Architettura pubblicitaria (advertising architectures), in “Casabella-Costruzioni”, n.159-160, 1941, a mono-graphic issue dedicated to the architecture of expos with rich iconography documentation edited by Bianchetti and Pea themselves. ; A. Bianchetti, Le oasi dell’autostrada (highway oasis), in “Quattroruote”, n.1, January 1960; A. Bianchetti, I ponti non convengono più (bridges are not convenient anymore), in “Modo”, n.18, April 1979.

Furthermore, it is opportune to cite: Italian luxury for export and those at home, too “Life” 26 September 1960; R. WEST, Italy: the new lean Bread of Eurocrats, “The Sunday Times”, 26 August 1962; C. MUNARI, Lo stile Pavesi (thepavesi style), in “Linea Grafica”, n. 5, September-October 1966, pp. 240-252; A. Colbertaldo, Quando si mangiava sopra i ponti (when we had lunch on bridges), in “Modo”, n. 18, April 1979; M. BELLAVISTA, Uomo di marketing prima del marketing (a marketing man before the times of marketing), in “Il Direttore Commerciale”, n. 7, 1988, pp. 16-21; B. Lemoine, I ponti-autogrill (the auto-grilll bridges), in “Rassegna”, n.48, December 1991.

We mention two more accounts of the actual phenomenon of the development of highway landscapes: P. DESIDERI, La città di latta. Favelas di lusso, Autogrill, svincoli stradali e antenne paraboliche (The tin city. Luxury Favelas, Autogrills, highway exits and parabolic antennas), Genova, Costa e Nolan, 1997; P. CIORRA, Autogrill. Spazi e spiazzi per la società su gomma (Autogrills, spaces and platforms for a society n wheels) , in Attraversamenti. I nuovi territori dello spazio pubblico (Crossings. The new territories of public spaes), edited by P. DESIDERI e M. ILARDI, Genova, Costa e Nolan, 1997.

[1] R. Banham, Megastructure. Urban future of the recent past, Londra, Thames and Hudson, 1976, the text does not illustrate these highway buildings.

[2] A. BIANCHETTI, Le oasi dell’autostrada (the highway oasis), in “Quattroruote”, n. 1, January 1960.

[3] A. COLBERTALDO, Quando si mangiava sopra i ponti (when we had lunch on top of bridges), in “Modo” n.18, April 1979.

[4] A. BIANCHETTI, C. PEA, Architettura pubblicitaria (advertising architecture), in “Casabella-Costruzioni”, n. 159-160, 1941.

[5] A. CANONICI, Pubblicità ed inconscio (advertising and the unconscious mind) in “Comunità”, n.60, 1958; A. BAROLINI, L’organizzazione dei centri di vendita in America, (the organization of sales points in America) in “Comunità”, n.67, 1959; R. BONELLI, Le autostrade in Italia (highways in Italy), in “Comunità”, n.86, 1961; G. TIBALDI, I consumi alimentari in Italia (food consume in Italy), in “Comunità”, n.115, 1963.

[6] Eero Saarinen, Charles Eames, Padiglione Ibm alla Fiera mondiale di New Yorkn(the Ibm pavilion at the worl expo of New York), 1964-65, well described by Kevin Roche, Charles Eames, in “Zodiac”, n.11, 1994.